The History Of Vaccines: 5 Little-Known Facts

May 31, 2017

When I began to understand the history of infectious diseases and the millions they killed over centuries, I was able to truly understand how miraculous the invention of inoculations and then vaccines truly were. This helped me change my hesitant mindset about vaccines. Understanding history is important, so today we are going to dig into five little-known moments in the history of vaccines.

The History Of Vaccines: 5 Little-Known Facts

1. Cotton Mather, a highly influential Puritan minister, became an early supporter of inoculations in colonial America. He was then viciously attacked.

In 1713, many of Cotton Mather’s family members were infected by the measles during an epidemic in Boston. He lost his wife, newborn twins, and a daughter, all within the span of a few weeks. It is no wonder why, when Boston was besieged by a Smallpox epidemic in 1721, Mather was a proponent of inoculation.

Variolation (the first method used to immunize an individual) was introduced in the American colonies when Cotton Mathers urged physician Zabdiel Boyston to variolate 248 people in Boston. Although only 3% of the inoculated population died, compared to 14% of the population who were not inoculated, there were still people who criticized Mather for promoting variolation. At one point, a primitive grenade was thrown through one of his windows with a threatening note attached, “COTTON MATHER, You Dog, Dam you. I’ll inoculate you with this, with a Pox to you.”

Mather was not dissuaded by this attack. He continued to promote variolation. This is what he said about the attack from those opposed to inoculations:

“I never saw the Devil so let loose upon any occasion. The people who made the loudest Cry…had a very Satanic Fury acting them…. Their common Way was to rail and rave, and wish Death or other Mischiefs, to them that practis’d, or favour’d this devilish Invention.” — Cotton Mather, quoted in The Life and Death of Smallpox by Ian Glynn and Jenifer Glynn

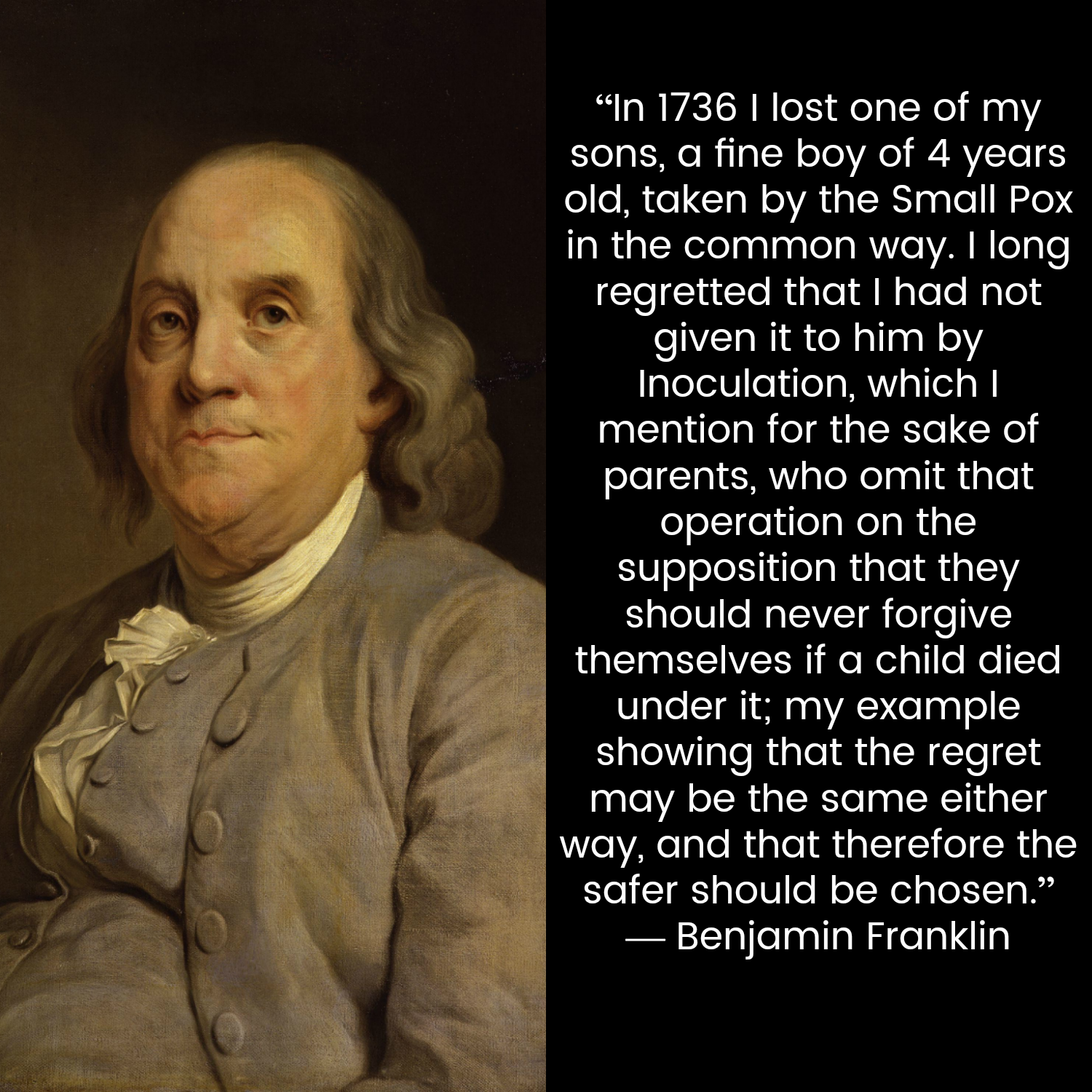

2. Benjamin Franklin’s son died of smallpox…and he regretted not vaccinating him.

On November 21, 1736, Benjamin Franklin’s four-year-old son, Francis Franklin, died of the smallpox. In response to rumors that his son had died despite inoculation, Benjamin later said:

Later, in 1759, Benjamin Franklin would even go on to distribute free pamphlets in the American colonies documenting the success of smallpox inoculation and encouraging parents to protect their children through inoculation.

3. Englishman Edward Jenner pioneered the world’s first vaccine… and saved millions of lives.

Edward Jenner began a 7-year apprenticeship for a surgeon at the age of 14 (which I love) and continued his studies at St. George’s hospital in 1770. While practicing at St. George’s, he met a milkmaid who was infected with cowpox, and believed this protected her from smallpox. Jenner, fascinated by this theory, began studying the link between cowpox and smallpox (we now know the cowpox virus belongs to the Orthopox family of viruses, including monkeypox and the variola viruses which cause smallpox).

In 1796, Jenner successfully inoculated eight-year-old James Phipps with matter from a cowpox sore on the milkmaid’s hand. He wrote a report of his achievement that was rejected by the Royal Society. Undeterred, Jenner self-published a pamphlet called, “An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a Disease discovered in some of the Western Counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of the Cow Pox.” A copy of Jenner’s pamphlet was given to Thomas Jefferson by Jenner’s nephew. In response, Jefferson wrote,

Sir: I have received the copy of the Evidence at large respecting the discovery of the Vaccine inoculation, which you have been pleased to send me, and for which I return you my thanks. Having been among the early converts, in this part of the globe, to its efficacy, I took an early part in recommending it to my countrymen. I avail myself of this occasion of rendering you my portion of the tribute of gratitude due to you from the whole human family. Medecine has never before produced any single improvement of such utility … You have erased from the calendar of human afflictions one of its greatest. Yours is the comfortable reflection that mankind can never forget that you have lived. Future nations will know by history only that the loathsome small-pox has existed and by you has been extirpated. Accept the most fervent wishes for your health and happiness and assurances of the greatest respect and consideration. — Thomas Jefferson, Letter, Monticello, Virginia, May 14, 1806, to The Rev. Doctr. G. C. Jenner

4. George Washington mandated vaccination in response to the British use of smallpox as a weapon of war.

In 1777, the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, George Washington, ordered mandatory inoculation for troops who had not previously been infected by smallpox. This was most likely a reaction to the inability of Benedict Arnold’s troops to capture Quebec from Britain the year before when more than half of the colonial troops had been infected by smallpox. At the time, a British commander used smallpox as a weapon by sending recently variolated civilians into Continental Army encampments. John Adams wrote about this outbreak,

“Our misfortunes in Canada are enough to melt the heart of stone. The smallpox is ten times more terrible than the British, Canadians and Indians together. This was the cause of our precipitate retreat from Quebec.” — John Adams, quoted in Ian Glynn and Jenifer Glynn, The Life and Death of Smallpox

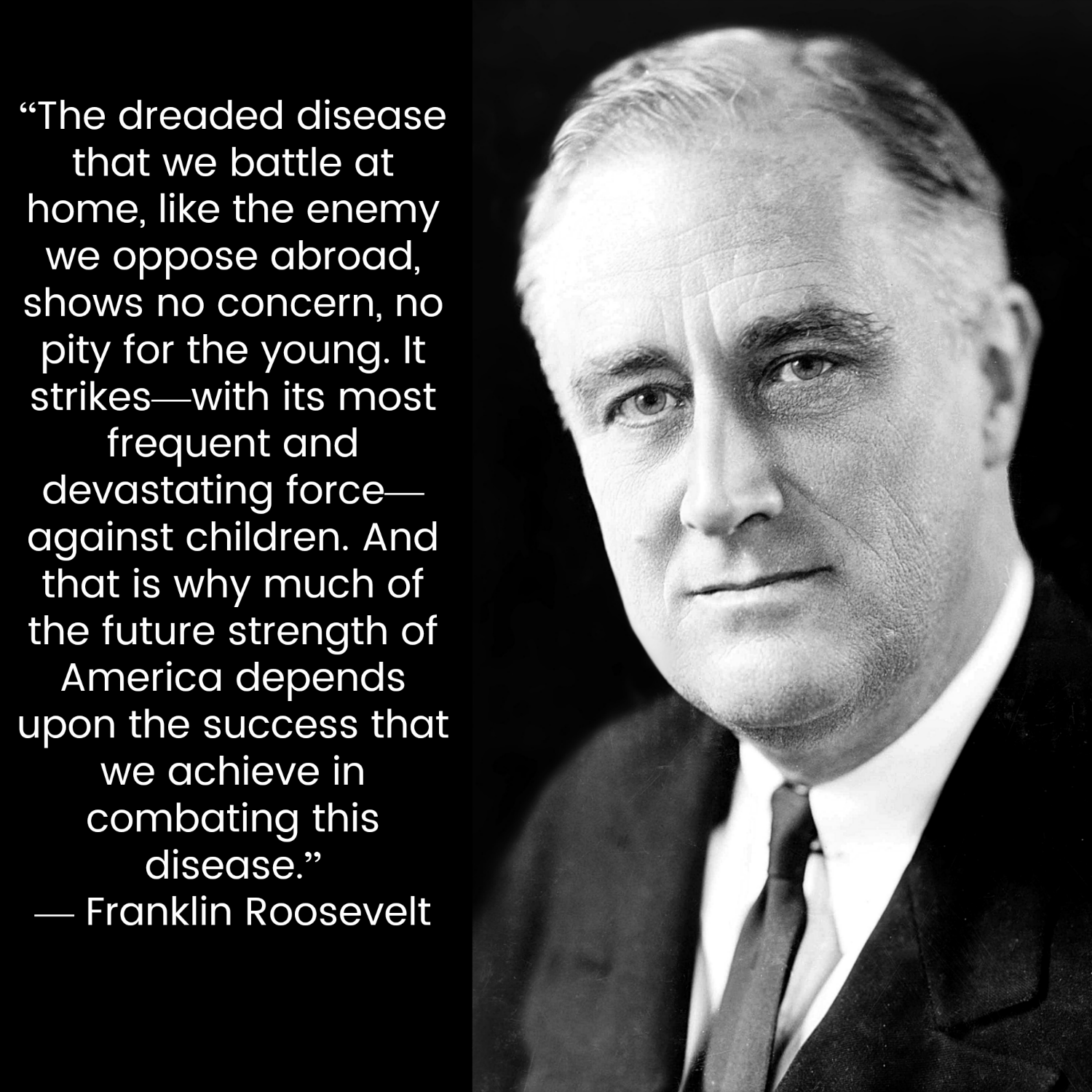

5. President Franklin D Roosevelt inspires Americans to fund polio vaccine research.

The first polio epidemic broke out in Vermont in 1894, but the disease continued to plague communities across the United States until it 1950 when 3 million people (2 out of every 100) were infected with polio. Polio is an enterovirus that is easily transferred and highly contagious. It typically starts with mild, flu-like symptoms, but can progress to muscle aches, spasms, and paralysis. 33,000 people, mostly children, were paralyzed from polio in the year 1950. President Franklin Roosevelt, whose legs were paralyzed by polio in his 30’s, made this statement comparing polio to the Second World War as it reached it pinnacle:

President Roosevelt got Americans involved in the fight against polio by starting the March of Dimes. He urged the country to send their dimes to the White House to fund polio vaccine research. This funding enabled Jonas Salk to develop and begin testing a polio vaccine in 1954. A Gallup poll conducted at the time noted,

“More Americans knew about the field trial of Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine than knew the full name of the US president, Dwight David Eisenhower.”

In 1955, Salk’s vaccine was licensed by the government, and between 1955 and 1962, after 400 million doses of the vaccine were given across the United States, the incidence of polio decreased by 90%.

This is only few small moments in the history of vaccines. For more fascinating and comprehensive information on the history of vaccines, I highly encourage you to visit the interactive timeline created by The History of Vaccines, an educational resource by The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

Author: Dani Stringer, MSN, CPNP, PMHS – founder of KidNurse and MomNurse Academy